海上低層雲の気候緩衝機構 Climate Buffering Mechanism of Marine Low-Level Clouds

Ebisuzaki (2023)が指摘したように、地球の気候は海上低層雲の雲アルベド効果によって強く緩衝されています。このため、地球に海洋が存在している限り、一部の研究者が心配している、二酸化炭素などの温暖化ガスの増加による暴走的的温暖化は起こる心配はありません。

As pointed out by Ebisuzaki (2023), Earth’s climate is strongly buffered by the cloud albedo effect of low-level marine clouds. Therefore, as long as oceans exist on Earth, there is no need to worry about the runaway warming driven by the increases in greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide that some researchers are concerned about.

雲アルベド効果による機構緩衝は、ノーベル物理学賞(2022年)を受賞したJohn Francis Clauser博士が、2024年7月7日にアメリカ合衆国テキサス州エルパソで行われた42nd Annual Meeting of Doctors for Disaster Preparednessという会合で”Climate Change is a Myth”という講演で議論しています。

Dr. John Francis Clauser, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics (2022), discuss the climate buffering due to the cloud albede effect in a lecture titled “Climate Change is a Myth” at the 42nd Annual Meeting of Doctors for Disaster Preparedness, held on July 7, 2024, in El Paso, Texas, United States.

この動画の1時間7-8分頃にあるスライドの”Sherwood et al. 2020 unnecessary assume ∂f_Clouds/∂T_surface=0″の下りが重要です。ここで、Clauser博士は、雲がサーモスタットの働きをするんだと繰り返しいっていますが、どのような機構で雲がサーモスタットになるのかは示していません。詳細はAppendix Cに書いてあるといっています。しかし調べてみると、発表資料の巻末のAppendix Cには、微分の連鎖率を使って海面温度の変化にしたがって雲の被覆率がどう変わるかを計算する必要があると述べるにとどまっています。

The slide shown at 1 hr 7-8 minuetes of this video is important, specifically the line stating “Sherwood et al. 2020 unnecessarily assume ∂f₍Clouds₎/∂T₍surface₎ = 0.” Here, Dr. Clauser repeatedly claims that clouds act as a thermostat, but he does not demonstrate the mechanism by which clouds function as a thermostat. He says that the details are written in Appendix C. However, upon examining the presentation materials, Appendix C at the end of the slides merely states that it is necessary to calculate how cloud coverage changes in response to changes in the sea surface temperature using the chain rule of differentiation, and does not actually provide a concrete physical mechanism.

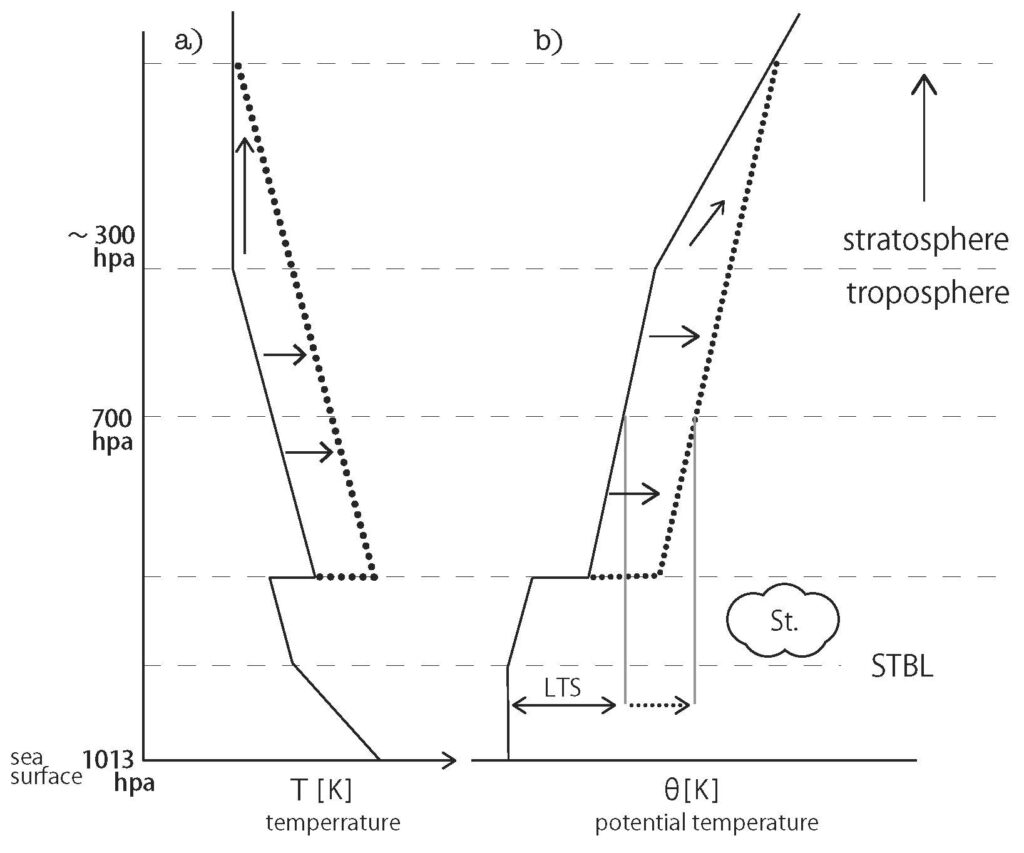

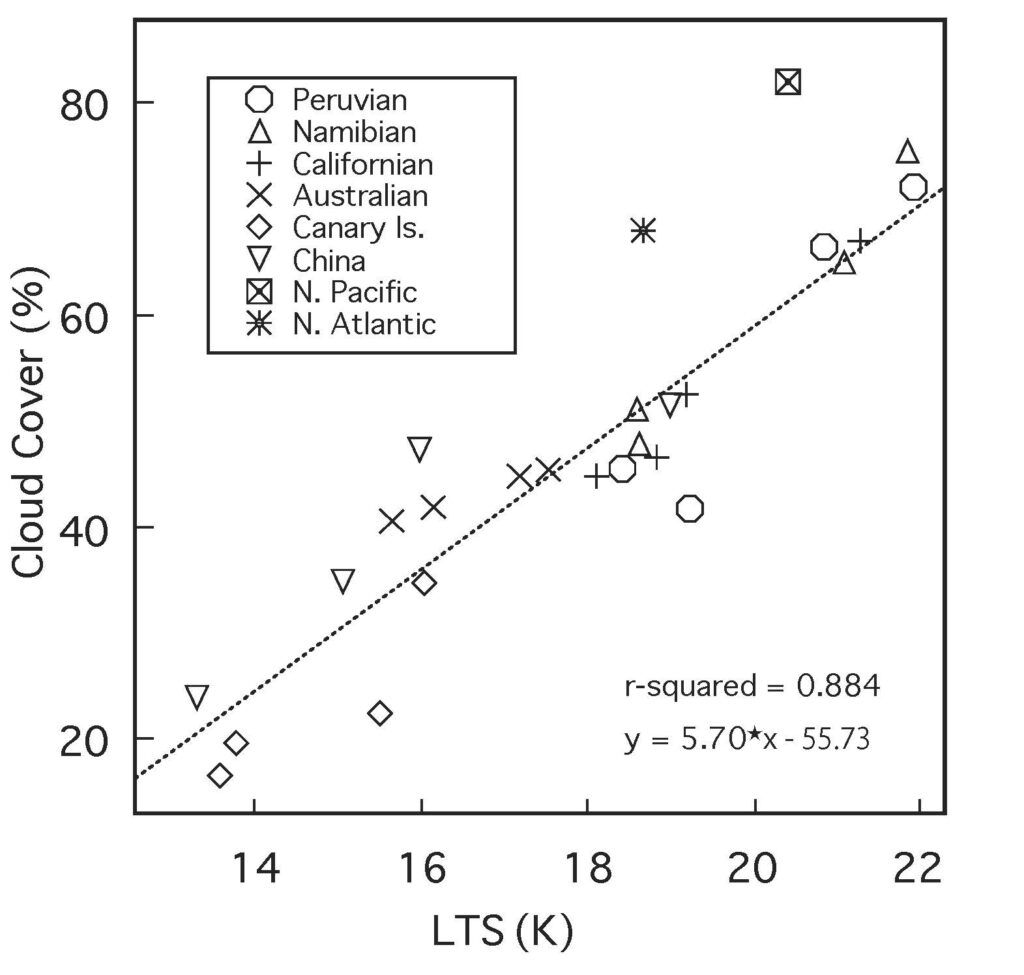

Ebisuzaki (2023)は、実際にこれがゼロではなく、正でしかもかなり大きいことを明らかにしました。彼は、温暖化ガスの増加すると海上低層雲の被覆率が増加し、地球アルベドが増加することを放射・対流平衡の変化を議論して示しました。ここで左辺の分母は、対流圏低層の温度です。温暖化ガス濃度の上昇による地球大気の応答は、まず成層圏・対流圏海面が上昇し、対流圏上部の温度が上昇(同じ圧力の場所で比べて)することから始まります。この温度上昇は放射・対流平衡に応じて次第に対流圏の下面に伝搬しますが、対流圏低層に温度逆転層があって雲冠境界層が存在する場合は、温度逆転層の上面で伝搬が止まってしまいます(Figure 1)。その結果、温度逆転層における温度差が増加し、対流に対して安定性が強化されるため、雲冠境界層がより長く維持されるようになり、雲被覆率(\(f_{\rm Clouds}\))が増加します。それを定量的に評価すると \[ \frac{∂f_{\rm Clouds}}{∂T_{\rm LT}}=5.7\, {\rm K}^{-1} \tag{1} \] を得ます(Ebisuzaki 2023)。ここで、\(T_{\rm LT}\)は温度逆転層の上の対流圏温度です。

Ebisuzaki (2023) demonstrated that this quantity is in fact not zero, but positive and quite large. By discussing changes in radiative–convective equilibrium, he showed that an increase in greenhouse gases leads to an increase in the coverage of low-level marine clouds, which in turn increases Earth’s albedo. Here, the denominator on the left-hand side represents the temperature of the lower troposphere. The atmospheric response of the Earth to an increase in greenhouse gas concentration begins with a rise in the stratosphere and the troposphere above the ocean surface, followed by an increase in temperature in the upper troposphere (when compared at the same pressure level). This temperature increase gradually propagates downward toward the lower troposphere in accordance with radiative–convective equilibrium. However, when a temperature inversion layer exists in the lower troposphere and a cloud-topped boundary layer is present, this downward propagation is halted at the top of the inversion layer (Figure 1). As a result, the temperature difference across the inversion layer increases, which enhances stability against convection. Consequently, the cloud-topped boundary layer is maintained for a longer time, leading to an increase in cloud fraction (\(f_{\rm Clouds}\)). A quantitative evaluation yields (Ebisuzaki 2023), where \(T_{\rm LT}\) denotes the tropospheric temperature above the inversion layer.

Figure 1. 温室効果ガスの増加による温位および気温の変化。温室効果ガスの増加により対流圏界面が上昇し、その結果として雲冠境界層上面より上の気温(および温位)が上昇する。この変化は放射対流平衡に至る時間スケール(数時間)で起こる。巨大な熱慣性をもつ海面の温度はこの速い動きに追随できない。この結果、対流圏界面に存在する気温逆転層における温度差が増加する。したがって、下層対流安定度(気圧700hPaと海面での温位の差: LTS)は増加し、対流圏界面上部に存在する下層雲(層雲と積層雲)はより長期にわたって維持される。 Changes in potential temperature and air temperature due to an increase in greenhouse gases. An increase in greenhouse gases raises the tropopause, which in turn causes an increase in air temperature (and potential temperature) above the top of the cloud-topped boundary layer. This change occurs on the radiative–convective equilibrium time scale (several hours). The sea surface temperature, which has enormous thermal inertia, cannot follow this rapid adjustment. As a result, the temperature difference across the inversion layer located at the tropopause increases. Consequently, lower-tropospheric stability—defined as the difference in potential temperature between 700 hPa and the surface (LTS)—increases, and low-level clouds (stratus and stratocumulus) that exist near the top of the troposphere are maintained for longer periods.

実際、海面温度が低い大陸の西海岸沖の海洋において、雲の被覆率は下層対流安定度(気圧700hPaと海面での温位の差: LTS)と強い相関を持っていることが確かめられています(Klein and Hartman 1993)。

In fact, it has been confirmed that over the oceans off the west coasts of continents, where sea surface temperatures are low, cloud cover shows a strong correlation with lower-tropospheric stability (LTS), defined as the difference in potential temperature between 700 hPa and the surface (Klein and Hartmann 1993).

Figure 2. Klein and Hartman (1993)は、低層雲の被覆率は地球上の多くの海域(図中の印で海域を表示)で低層対流安定度(LTS)と強く相関することを明らかにした(Klein and Hartman 1993をもとに改変) Klein and Hartmann (1993) showed that the fractional coverage of low-level clouds is strongly correlated with lower-tropospheric stability (LTS) over many oceanic regions of the globe (the oceanic regions are indicated by symbols in the figure) (modified from Klein and Hartmann 1993).

この大気中高層(\(p<700 \mathrm{hPa}\))の温暖化による雲の増加を考慮すると、放射・対流平衡を考慮した実際の温度上昇\(\Delta T_{\mathrm{RCE}}\)は:

Taking into account the increase in clouds due to warming in the upper atmosphere (\(p<\mathrm{700hPa}\)), the actual temperature increase \(\Delta T_{\mathrm{RCE}}\) under radiative–convective equilibrium is:

\[

\Delta T_{\mathrm{RCE}}

= \frac{\Delta T_{\mathrm{GH}}}

{1 + 2.1

\left( \frac{\eta}{0.7} \right)

\left( \frac{A_{\mathrm{cloud}} – A_{\mathrm{sea}}}{0.7} \right)}

\tag{2}

\]

となります。ここで、\( \eta \) is 低層雲が被覆する海洋の割合です。このように、 放射・対流平衡(雲の増減)を考慮した実際の温度上昇\(\Delta T_{\mathrm{RCE}}\)は、そうしなかった場合の値\(T_{\mathrm{GH}}\)の約3分の一になります。ここでは考慮していない他の効果を加えると、さらに5分の一程度になる可能性が高いです(Ebisuzaki et al. 2023)。

Here, η is the fraction of the ocean area covered by low-level clouds. In this way, the actual temperature increase\(\Delta T_{\mathrm{RCE}}\), which accounts for radiative–convective equilibrium (including changes in cloud amount), becomes approximately one third of the value \(T_{\mathrm{GH}}\) obtained when such effects are not considered. Furthermore, when other effects not considered here are included, it is likely to be reduced to about one fifth, further (Ebisuzaki et al. 2023).

1) Ebisuzaki T. 2023: 戎崎俊一、2023,海上低層雲による気候変動緩衝(Climate Buffering of Marine Low Clouds)、TEN (Tsunami, Earth, and Networking), 4, 52-67 (in Japanese). English translation is available at https://science.gakuji-tosho.jp/articles/4728

|

TEN vol.4

|

書籍版『科学はひとつ』のご案内

戎崎俊一 著

学而図書/四六判 並製320頁/本体2,400円+税

12年にわたり執筆されてきた記事を精選し、「地震と津波防災」など全9章に再編。すべての章に著者書き下ろしの解説を加えて集成した一冊。